|

Fellows News: |

|

Tom Averill, English, announces publication of his newest book, a collection of short stories, Ordinary Genius (University of Nebraska Press). Tom read from his work in the Kansas Room, Memorial Union, on April 5. For more information about the book see his website. Tom Averill, English, announces publication of his newest book, a collection of short stories, Ordinary Genius (University of Nebraska Press). Tom read from his work in the Kansas Room, Memorial Union, on April 5. For more information about the book see his website.

Marydorsey Wanless, Art, had three photographs of the prairie accepted for publication in the Plains Song Review, Volume VII. It is a publication of the Center for Great Plains Studies at the University of Nebraska. The photographs and other art will be on display for two weeks at the Great Plains Art Gallery, 1155 Q Street, Lincoln, NE. A reception and reading will be at the Gallery on Thursday, April 21, 2005 at 7:00 pm. For more information contact cgps@unl.edu Marcia Cebulska, who is William Inge Center’s playwright-in-residence, announced plans for the Inge Center, through its director, Peter Ellenstein, to forge a possible partnership with Washburn University. Marcia would write a one-character play on the life of William Inge to premiere at the William Inge Theatre Festival in 2006. |

Margaret Wood, Sociology/Anthropology, is involved in organizing the 64th Conference of the Plains Anthropological Society, to be held in Topeka in 2006. Margaret is heading fundraising for this event. Tom Averill, English, is planning a fall map colloquium, tentatively titled, “From Three Dimensions to Two: Mapping, Charting, Representing, Prediciting and Imagining the World.” Tom reports having a wonderful response to the call for papers, with an evaluation soon to narrow the colloquium to a group of 14-16 scholars. Marguerite Perret, Art, and the Washburn Art Department hosted an exhibit of quilts and photo-silk-screened images by fiber artist Joleen Goff. “Farm Stories: a Place of Belonging” featured imaged-depicting themes from Goff’s grandparents’ farm in Kansas and was part of a Fiber Arts Forum held in February 2005. Further information and photos of the forum are available online. Tom Schmiedeler, Geography, introduced Don Stull, Professor of Anthropology at Kansas University, as the Kansas Day Speaker. Dr. Stull spoke on Friday, January 28, on “Meat-packing and Mexicans on the High Plains: from Minority to Majority in Garden City, Kansas.” Dr. Stull’s visit to Washburn was funded by the Center for Kansas Studies. |

Prairie Cathedrals without Congregations |

|

great distances. The workaday operations of the grain elevators could cease, and they would still serve a vital function on the prairie simply by being visible” (Gohlke, 22-23). |

|

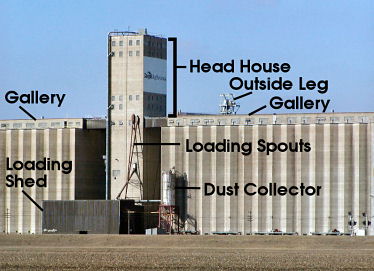

“...generations of painters, novelists and photographers have found in grain elevators ‘not architectural maxims, but symbols of life on the Great Plains.’” As the grain conveyor belt begins its descent at the top of the headhouse, the buckets empty their contents into the “garner,” a hoppered holding tank that sits directly above another hoppered tank attached to the framework of a Fairbanks scale. As the garner fills, the next operation involves opening its bottom slide to allow grain to flow into the scale hopper. A decade or so ago, this was done manually by a scale operator on the “scale floor” immediately below the garner floor. In most terminal elevators today, however, slides are remotely controlled either by an operator in an office somewhere on the ground or by highly automated computerized systems. As the scale fills and approaches an 80,000 to 90,000 pound draft weight, one of two necessary to fill most hopper cars, the automated systems precisely balance the scale at the desired weight. A draft ticket is electronically punched and the scale slide is then opened to its maximum. As the grain flows from the scale hopper the garner hopper continues to fill with the next draft.

Thus, the garner, in its holding tank capacity, allows grain to flow continuously, sometimes for hours on end when elevators are loading so-called “unit trains.” (Next: see "Loading operations...") |

|

them. With increasing competition among railroad, barge and truck transportation, a new type of grain elevator—the subterminal—has emerged as a hybrid between country and terminal elevators. Their geography, at “access points convenient for assembling shipments via both rail and highways” is often in “open country away from towns” (Hudson, 100-101).

|

Prairie Cathedrals... Bibliography

|

|

Banham, Reyner. The New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic?, (Reinhold: New York), 1966. Quoted in Carney, p.1. Carney, George O. “Grain Elevators in the United States and Canada: Functional or Symbolic?,” Material Culture, 27(1995): 1-24. Corbusier, Le. Towards a New Architecture, trans., Frederick Etchells (1931). Gohlke, Frank. “Measure of Emptiness,” In Measure of |

Emptiness: Grain Elevators in the American Landscape, (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press), 1992: 14-85. Hudson, John C. “The Grain Elevator: An American Invention,” In Measure of Emptiness: Grain Elevators in the American Landscape, (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press), 1992: 88-102. Riley, Robert B. “Grain Elevators: Symbols of Time, Place and Honest Building.” American Institute of Architects Journal, November, 66(1977): 50-55. |

Kansas Studies Courses— |

Fall 2005 offerings include:

Kansas Studies minors at Washburn University, upon graduation, are expected to:

|

| DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY |

|

This class will be working with the Kansas State Historical Society to make a photographic documentary of small towns in Northeast Kansas. The project will conclude with a traveling exhibition, and copies of the work will be donated to the Kansas Historical Society for its permanent collection.Students will be working in pairs, with each pair documenting one town for the semester. Participants will receive instruction in historical research, history of documentary photography, interviewing techniques, structure of prairie towns, architecture, photography, etc. |

There will be a field trip to the Spencer Museum to see the Pennell Documentary Photography collection, and Jim Richardson of National Geographic will spend a day with us discussing his documentation of Cuba, Kansas and critiquing student work. Prerequisites: AR 220 Photography 1 or consent of instructor. Students will need their own 35mm Single Reflex Lens camera that uses film. For information, Marydorsey Wanless, 231-1010 ext. 1632 or marydorsey.wanless@washburn.edu. |

|

Hicks Block, Topeka, auctioned |

|

| On March 20, 2005 the Hicks Block, 600 S.W. 6th, Topeka, was auctioned. Ruth Martin of Topeka won high bid of $110,000. The seven row houses were built in 1888-89 for $50,000 by Elhanan Hicks. After a real estate depression, Hicks lost the property and each three-story (plus basement) row house was owned separately. By the 1960s, Marjorie Dove, born at 525 S.W. |

Tyler (a row house within the Hicks Block) and her mother owned all of the houses. Eventually each was divided into four apartments. The building earned a place on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977. Dove died last year and the property was owned briefly by John Clinkenbeard. |

espite the popular view of grain elevators as agricultural icons, their form is far more powerfully driven by utilitarian aspects of which the public is largely unaware because few people have ventured inside them. Grain elevators became components of a collection system through which a region's crops could be funneled to distant markets. As upright, concrete structures they were born of the necessity for eliminating the more labor-intensive movement of grain stored in bags in flat, open-storage units. Concrete elevators were a significant improvement over earlier upright wood and later ironclad elevators because they were less prone to insect infestation and to fire, which increased insurance rates. Concrete became the most popular building material for elevators by the early 1900s with the development of an innovative, concentric, double-ring, construction form, which created a tank in “one solid and continuous piece of concrete without joints or patches” (Carney, 8-10). Physics, too, played a role in the evolution of concrete elevators. According to Riley, “internal friction produces an arching effect within the mass of grain, which in turn is partly transferred by friction to a downward vertical compression in the bin walls.” The result was that “the floor can stand unsupported over an emptying trough” and “walls can be thin. This was particularly important in encouraging the early use of concrete, strong in compression but weak in tension. Thus, the striking verticality of grain elevators is a direct function of the static properties of the grain itself” (Riley, 51).

espite the popular view of grain elevators as agricultural icons, their form is far more powerfully driven by utilitarian aspects of which the public is largely unaware because few people have ventured inside them. Grain elevators became components of a collection system through which a region's crops could be funneled to distant markets. As upright, concrete structures they were born of the necessity for eliminating the more labor-intensive movement of grain stored in bags in flat, open-storage units. Concrete elevators were a significant improvement over earlier upright wood and later ironclad elevators because they were less prone to insect infestation and to fire, which increased insurance rates. Concrete became the most popular building material for elevators by the early 1900s with the development of an innovative, concentric, double-ring, construction form, which created a tank in “one solid and continuous piece of concrete without joints or patches” (Carney, 8-10). Physics, too, played a role in the evolution of concrete elevators. According to Riley, “internal friction produces an arching effect within the mass of grain, which in turn is partly transferred by friction to a downward vertical compression in the bin walls.” The result was that “the floor can stand unsupported over an emptying trough” and “walls can be thin. This was particularly important in encouraging the early use of concrete, strong in compression but weak in tension. Thus, the striking verticality of grain elevators is a direct function of the static properties of the grain itself” (Riley, 51). rain elevators are primarily storage facilities, but the advantages of the modern terminal elevator are realized in the movement of grain. Movement is that of a rectangular circuit. Let's plug into the circuit at the tracks where workers are unloading a series of “hoppers,” a type of rail car with funnel-shaped compartments used to haul bulk material. Hoppers, which originated with the Southern Railway in the early 1960s and rapidly replaced box cars that were far more labor intensive to load and especially to unload, can hold up to four thousand bushels of grain (Hudson, 99-100). When the compartments of the hopper car are aligned over the “pit,” workers open the hopper bottom or "slide" and the grain falls by gravity through the grate covering the pit to a horizontal conveyor belt. The grain quickly moves inside to the “leg,” a vertical belt two to three feet wide with metal “buckets” bolted to the belt, all of which is housed in a rectangular, box-like enclosure of heavy gauge sheet metal. A 100 to 150 horsepower motor drives the belt at a high speed so that grain flowing off the end of the horizontal belt can be picked up by the buckets and transported upward about two hundred feet to the top of the “head-house,” the rectilinear structure rising above the circular bins.

rain elevators are primarily storage facilities, but the advantages of the modern terminal elevator are realized in the movement of grain. Movement is that of a rectangular circuit. Let's plug into the circuit at the tracks where workers are unloading a series of “hoppers,” a type of rail car with funnel-shaped compartments used to haul bulk material. Hoppers, which originated with the Southern Railway in the early 1960s and rapidly replaced box cars that were far more labor intensive to load and especially to unload, can hold up to four thousand bushels of grain (Hudson, 99-100). When the compartments of the hopper car are aligned over the “pit,” workers open the hopper bottom or "slide" and the grain falls by gravity through the grate covering the pit to a horizontal conveyor belt. The grain quickly moves inside to the “leg,” a vertical belt two to three feet wide with metal “buckets” bolted to the belt, all of which is housed in a rectangular, box-like enclosure of heavy gauge sheet metal. A 100 to 150 horsepower motor drives the belt at a high speed so that grain flowing off the end of the horizontal belt can be picked up by the buckets and transported upward about two hundred feet to the top of the “head-house,” the rectilinear structure rising above the circular bins.

his basic system of grain movement has evolved to the point where large terminal elevators are capable of loading 120-car unit trains within a day. The special rates given by railroads for unit trains have provided the large terminal elevators with significant competitive advantages over the older country elevators whose capacities are far too small for them to be eligible for the cheaper rates. Through time, many of the country elevators have become redundant and railroads have abandoned the branch lines that served

his basic system of grain movement has evolved to the point where large terminal elevators are capable of loading 120-car unit trains within a day. The special rates given by railroads for unit trains have provided the large terminal elevators with significant competitive advantages over the older country elevators whose capacities are far too small for them to be eligible for the cheaper rates. Through time, many of the country elevators have become redundant and railroads have abandoned the branch lines that served

![[wheat graphic]](spring2005/wheat.jpg)