"The Man Who Conquered Reality: A Look into the Unusual Mind of Max Yoho"

"Never let reality limit your life; reality gets in the way." - Max Yoho

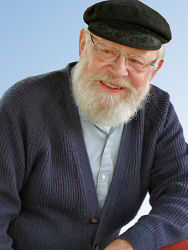

Yoho, now a gruff seventy-nine-year-old man, has had two jobs since graduating from high school: as a machinist for 38 years and as an award winning Kansas author with six published books as well as multiple other publications, including poetry and short stories.

It was while he worked at the Bracket Stripping Machine Company, which manufactured book binding equipment, that Max was first introduced to great literature: in the form of Voltaire. The factory received unbound copies of Candide, one of which he took home and read. "It stretched my mind, but my education has come half-handedly," he says.

Max has known me all my life; although, before conducting this interview, I barely knew him. I knew he was a good friend of my mother, a well-known Kansas author, and (from what I'd heard) an interesting character, but what I didn't know was that Max had been a part of my life since the day I was born. In fact, when I was only seven days old, he dedicated and performed a song in my honor. Its title was "Postpartum Blues." My mother has the recording. I hemmed and hawed a lot about choosing a subject for this interview. I considered a woman who could write backwards, a number of good friends, and a man who had blinded an intruder with his bare hands, before Max came to mind. When I suggested setting up an interview with Max, my mother was delighted. "In my opinion," she told me, "Max is as interesting as anyone of his characters; and that's saying a lot."

As I sit across the room from Max, lounging comfortably in an armchair, he hands me a copy of his latest book, Me and Aunt Izzy. The photograph of him on the back of his novel is reminiscent of a salty old ship's captain, ironic for someone with the last name Yoho. On the book jacket, he has the same thick white beard and large rectangular glasses as he does now, the only difference between the man in front of me and the man in the photo is the sailor-esque hat covering his bald head. I flip the book over and see a familiar scene: the same dresser, statue, and slinky tabby cat adorning the cover of the book as are sitting discreetly in the corner of his living room. "Carol (my wife) does all the artwork for my books," he explains. You can tell from his decor that Max is a lover of the arts. Max himself was a machinist and has turned his talent for metalwork into a creative hobby. The masterfully crafted mantelpiece adorning the fireplace across the room was hand-built by Max.

A couple of intricate kaleidoscopes catch my eye. One is an old Victorian style instrument in a dark cherry-colored wood; the other is a more modern style. I ask if! can see them and peer into the modern-style one as he turns the dial. The glass shards and beads inside the kaleidoscope shift and tumble. I turn to the Victorian style one. It's truly masterful. Three different cogs turn to make the beads shift. "This was the first one I made." He informs me. "I made the glass too thick so it doesn't turn as well."

Paintings from his first wife, current wife, and current wife's ex-husband also decorate the room. Becky Wright painted a beautiful floral chalk picture hanging near the mantle which he bought for Rosemary (his first wife) for Christmas one year. The water color flowers hanging on the wall near the front door was Rosemary's last painting before she died.

Max didn't really begin writing until he was in his 50s, he explains. He had an interest in writing his entire life but he worked as a machinist in order to support himself. "I never really thought about being a writer. I enjoyed it, but I had a family coming along and I had to make a living."

"You can't be a starving artist and raise a family," I comment.

Max smiles and says matter-of-factly, "They frown on letting your kids starve, yeah. Kansas has some of the dumbest laws."

Growing up, Max had one sister who was four years older than he. His father worked for the Santa Fe Railroad and his mother was a housewife. "I had a kind of naive childhood, very innocent. I grew up in a small town. I was free to ride around town and stop at the neighbors and ask for a drink of lemonade."

He was born in Colony, Kansas in 1934 and moved to Atchison with his parents in 1944 where he finished grade school. He graduated from Topeka High School in 1953. He took some classes at Washburn University some years later. "I started taking classes at Washburn several years after I got out of high school because I began to realize how stupid I was, how dumb I really was, how little I really knew." It was at Washburn that he met a woman that would inspire him to pursue writing, his Freshman English teacher, Marilyn Jurich. "I had this wonderful teacher, who wasn't much older than me, but was very well educated," Max says. "She understood my sick sense of humor." When he wrote his first book, The Revival, he wanted to dedicate it to her and sent her a letter asking for her permission. "She said 'I would be honored—but this isn't the kind of book I like at all.'" They are still in contact today.

Max began writing his first book in 1989 after a man he worked with came to work bragging that his wife's poems were being published. Max asked if he could see her work and sent her his. She said, "You're a writer; you need to meet some friends of mine." Shortly after that he became involved in A Table for Eight, a local writers' group. He brought pages from The Revival weekly to this group where he was encouraged to submit it for publishing.

"I write humorous fiction more than anything," Max says when asked about his work, "[but) I've done a little bit of everything. I've done a little bit of poetry." His favorite thing to write is short stories. "It helps you to distil your writing and get rid of any superfluous thoughts." Several of his books focus on a protagonist who is an eleven or twelve-year-old boy. "I guess you could say [my books are] coming of age books. ...I find the viewpoint of a boy of that age interesting. It's different from an adult's viewpoint; it can be sad or it can be humorous. ...A boy that age is beginning to have very ambivalent feelings about girls. You still kind of hate them a little, but they're beginning to look better."

Max doesn't think too much about what will sell, he writes for his own enjoyment and for the enjoyment of others.

"My own feeling is to let my mind wander and not be bound. ...A lot of people rely on straight lines, straight narratives, and that's not me. Another thing I refuse to do is write in a particular genre. I have kind of done that by accident…but I think I got out of that when I wrote With the Wisdom of Owls, which caused a lot of heads to shake and wonder where my mind was, but some said it was my best book."

Max does, however, have to do some promotion for his work. "I've probably done 150 [events] by now," he informs me. "The world of publishing has changed to a point where publishers don't do much to promote their author's work. Authors really have to present their own work. When I speak, I sell books. People do not buy poetry—poetry does not sell—but when I'm speaking and I read my poetry, I sell books."

Promoting isn't Max's favorite; he doesn't enjoy the business side of authorship, but he does enjoy connecting with the public. "Carol says I'm half hermit and half ham. My basic feeling is that I am a hermit. I am not a social person. I don't belong to anything, except the Kansas Authors Club, but I do enjoy speaking. Carol does all of the business side of it. I don't do any of it. I don't push myself; it makes me cringe to do that. But it's an important part."

His true inspiration for writing is a desire to make people happy, to find his own happiness, and to make peace with difficult memories of his past.

"I suppose [I began publishing] because people liked what I was writing ... I believe it's natural that we like to be appreciated for what we do. I'd gone through a bad time, my wife had cancer, but she ultimately took her own life, and I came home and found her dead. [My books] seemed to make people laugh at times and cheer them up. It's given me a purpose in life. It's something I can do, something I enjoy." In Max's older "crippled" years writing has been a hobby that has been easy to maintain. His workshop, where he used to make his fine wooden decor, has been out of use for years, piled with scrap metal and junk, collecting dust. His antique horn collection has been mostly packed away in boxes, given away, or sold. He doesn't have the energy to polish and maintain them anymore. But writing will always be a safe haven for him, a place where he can go to let his mind run free for a bit.

Max is doing a little writing currently but he doesn't know if it will become a book or not. ''I'm often the last one to know," Max says. "I've never been a driven writer. I write for fun; when it's not fun, I don't write."

As I'm getting ready to leave I thank him for his time and he mentions a quote he once saw on a man's gravestone: "He's done his damnedest damnedest; angels can do no more." I don't understand exactly what that means, but it seems to fit Max quite nicely.