|

|

| Biography |

|

| |

Edgar Wolfe was born in Ottawa, Kansas on August 27, 1906. He attended the Univeristy of Kansas in Lawrence where he earned a B.A. in English. With his degree he taught high school in rural South Dakota. In 1929 he married Nina Ruth Winters. Wolfe eventually returned to Kansas where he worked as a teacher and a door-to-door salesman. In 1935 he quit work as a saleman and moved to Kansas City, Kansas where he worked as a caseworker for the Kansas Emergency Releif Commission.

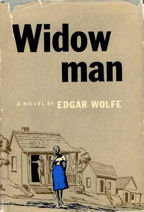

He returned to the University of Kansas in 1947 where he earned his M.A. He would stay at the University of Kansas and teach creative writing, first as an associate professor and then as a professor. Wolfe published Widow Man in 1953 which was on the New York Herlad-Tribune's list of Best Books of 1953. He would go on to co-author and publish an English textbook, Write Now in 1954 as well as his novella, Trial By Ice in 1961.

Edgar lost his wife in 1973. He retired from the University of Kansas in 1977 and married Marguerite Everett that same year. In 1986, Edgar published a collection of stories and a narrative essay entitled To All the Islands Now and a special edition of Cottonwood magazine was dedicated to Wolfe that winter. Edgar Wolfe died in 1989, the same year a volume of his poetry, The Almond Tree, was published.

Return to Top of Page

|

|

|

Bibliography ( - housed in Thomas Fox Averill Kansas Studies Collection) - housed in Thomas Fox Averill Kansas Studies Collection) |

|

| |

Books:

The Almond Tree (Woodley Press, 1989) The Almond Tree (Woodley Press, 1989) To All the Islands Now (Woodley Press,

1986) To All the Islands Now (Woodley Press,

1986) Window Man (novel) (Little Brown and Company,

1953) Window Man (novel) (Little Brown and Company,

1953)

Return to Top of Page |

|

|

| Selected Poems

|

|

| |

Each Man is an Island

To all the Islands

now I cry

My lesson in geography.

We are all, however close,

apart

and disparate, but yet alike,

being of the one great,

growing

Archipelago of Man,

which, crowding close, lies dense

in groups,

or else, much thinned, strung out for many

a

thousand miles across the reaches

of our sea, but still, alas, in

every

case, above the Primal Fault,

whose constant breakings,

tiltings, crackings

account for all these quakes we

have,

upheavals, tidal waves, and storms,

and even cause that

we must each

of us in time be taken down,

immersed and

drowned, while constantly

new islands are upheaved to

break,

in every season, every weather,

the astonished surface

of the sea.

South Wind

What birds are these that sing?

What wind

that climbs the hill and seems so glad

to find on it

the sun that she

will grant a dance to any tree,

a kiss to any

creature, however

old or gaunt and thin, whose love,

perhaps,

in autumn died, well-grieved

and long-bemoaned, under the

cold

stars or under the dim, gray sun

or snowy sky, but now he

wakes,

renews desire, sighs to the wind

soft words and begs

her to stay (her

of the warm Southland passing, who,

asked,

may choose to stay). But how can life

rise up again in

such a heart

as his? One with the grass the mystery

is, with

everything that's green,

with warmth and light and shadows

battening.

Above his head the pine song,

another in his heart,

of love

and life and all that comes with spring.

Return to Top of Page

|

|

| Original Jacket and Excerpts from

Widow Man |

| |

Chapter 2

"'Color don't really make no differ'nce in people. It's only what people thinks that does it. Take these folks here in this bus now. They'd look at Dioal an' me an' never could understand why we'd do it, or why she was better'n anybody else for me. They couldn't understand nothing. But when they look at me an' the old lady, maybe they do grab onto their noses an' breathe mighty scant an' set back there an' laugh their sleeves full, but here's the thing of it. There's some of 'em can put theirselves in our places just 'cause they thing we ain't all ways differ'nt. The color o' the package tell 'em the contents's the same. They think they could git old an' silly like her an' not git half looked after right. Or they could git a leg off like me an' then git sadled with an old crazy woman on top o' that. So they sorta see how it is. That's what bein' white is. It's bein' understood.'"

Chapter 3

This time he did not watch her go. He sat glowering, hurt an miserable and mean. He wanted to give pain and to receive it. If he could only, just once, plant a firm and improving kick on Mrs. Tunesie Graybill's all-too-fetching backside! Let her pay him back then all she liked. Let her snatch his cherished crutch and splinter it, for good and all, upon his useless old skull. It would help.

Nothing of her remained except the pie. It was her gift and it had pleased him, as she had. He leaped up, thinking to carry it to the garbage pail and hurl it savagely in, but his chair caught somehow and tipped over. Grabbing for it, he lost balance, fumbled his hold on his crutch, and sprawled headlong over the chair and down upon the fallen crutch and floor.

He was hurt and bruised, but now the realness of his pain seemed to cool his temper rather than make it worse. While he felt of his bruises and said the words that soothe, he was collectting his wits, and even as he hopped up on his foot again, retrieved his crutch, and righted the chair, he thought of something.

Why had Tunesie baked him a pie and washed his dishes? Becasue she was husband-hunting. Because he needed a wife. She had said that he did, and she had just been showing him her wifely accomplishments. Even in her effort to get him to spend his money on an artificial leg he could see her promoting him into that "steady wukin' man" whom seh coveted adn who didn't alwasy see her. If she married him, old cripple though he was, and, upon trial, he didn't satisfy, he imagined thathe white man could, like the two Negroes before him, become an ex-husband of Mrs. Tunesie.

Chapter 4

"'If I want to be white, really white, what I got to do is git out where I can be white --- leave Quarry Hill. Just sell out an' go, whether I want to or not. Live with white people, talk with'em, do things together, go to white churches, git acquainted---everything. Start all over'"

It was astonishing and appalling, too, but it was the thing to do. He seemed to see it clearly now. Leave the Hill! Leave his home. Leave Diola's home. Since she was dead, it was the thing to do. Leave the Ewings, the Johnsons, the Thompsons, all his old neighbors, everybody. Get away from Mrs. Bradford. Leave Tunesie. Then she would see.

Return to Top of Page

|

|

|

| A Poem for Edgar Wolfe

by Thomas Fox Averill |

|

| |

How to Grow Old Playing Handball, from Cottonwood Review 34, 1984

First, quit diving for the ball.

Let your aging

body teach you what your mind already knows:

A good player lets

the ball come to him.

When it does come, hit it well--

Every

shot must be the last.

Conserve what strength you have.

Get

used to going from tired to more tired.

Let your eyes learn the

slow burn of sweat.

Let your shoulers wince as your arms move in

that high arc above your head.

Let your kneeds stiffen

and

Stalk the ball in a crouch, neither straightening nor

stooping,

Compromised, but always at least half

ready.

Then quit playing singles. In doubles your partner can

take up your slack.

You won't see the ball as you once did.

It

will blur, then be there in your hand, a small black

surprise.

That fine spin,

That six-inch hop left or

right,

That calculated deadness from a corner shot,

That

crackling kill-shot off the back wall:

All of these will be

beyond your control as

The ball you've hit bounces straight from

the wall into

Younger, more certain hands.

When your

arthritic shoulders keep you from lifting your arms,

You will

look like a small bird, flapping your short reach furiously at your

sides.

When your neck is a stiff column,

You will rotate your

body with the slow precision of a periscope.

When your breath

comes short,

You will rest longer between games, between

points.

Play only three times a week, then twice, then once, then

sporadically.

Last, you will sit stiff in some chair.

Its

squeaks will always remind you of new tennis shoes on varnished

courts.

Your heart will thud like leather gloves striking that

small rubber ball.

The small of the court will live in your old

man's nostrils.

Return to Top of Page |

|

| An Edgar

Wolfe Chronology |

| |

1906--August 27, born Edgar Wolfe at 722 West

Sixth Street, Ottawa, Kansas.

1915--Moved to a

six-acre, "miniature farm" at 518 Beech Street,

Ottawa.

1924--Graduated from Ottawa High

School.

1924--Attended the University of Kansas,

Lawrence, Kansas, graduating in 1928 with a major in

English.

1928--Took a teaching job at

Stoneville, South Dakota, High School, teaching English, Latin,

Geometry and Bookkeeping.

1929--Married Nina

Ruth Winters

1930--Took a teaching position in

Axtell, Kansas.

1931--Took a teaching position

as the teacher at Weta, South Dakota, High

School.

1932--Returned to the University of

Kansas to begin work on a Master's degree in

English.

1933--Spring, won intramural singles

one-wall handball championship as a graduate student at the

University of Kansas.

1933--Summer, moved to

Ottawa to tlive with parents due to lack of

money.

1933--Fall, contracted to sell household

products for J.R. Watkins, Co., of Topeka, Kansas,

door-to-door.

1935--Quit sales, movedf rom

Topeka to the Argentine District of Kansas City, Kansas, and took a

job in Wyandotte Coutnry as a caseworker for the Kansas Emergency

Relief Commission.

1939--Reassignedto Rosedale

District. Ed's first purchased home was on Nearman Road, now 2220

North 55th Street.

1942--Left welfare work to

participate as he could in the war effort (poor eyes kept him from

enlisting) by teaching English and remedial work in the three R's to

courtmartialed prisoners at the U.S. disciplinary Barracks at Fort

Leavenworth, Kansas.

1947--Returned to the

University of Kansas with an assistant instructorship to again do

graduate work towards a Master's degree in

English.

1948--Won the Carruth Poetry

Prize.

1949--Won the William Allen White prize

for his novelette, I'd Shelter

Thee.

1949--Became a full-time Instructor

in the remedial English program, teaching 1-A

English.

1950--Finished Master of Arts degree in

English from the University of Kansas

1951--Won

the William Allen White Prize again, this time for the manuscript of

a novel, Widow Man.

1953--Published

Widow Man with Atlantic Monthly Press in conjunction with

Little, Brown and Company. Widow Man was listed on the New

York Herald-Tribune's prestigious list of Best Books of

1953.

1954--Wrote and published, as co-author

with A.C. Edwards and Natalie Calderwood, an English textbook,

Write Now (New York: Henry

Holt)

1958--Became Assistant Professor of

English.

1958--Ed's father died at age 82 in

Eudora, Kansas.

1961--Published a novelette,

Trial by Ice, in the anthology Kansas Renaissance,

ed. Warren Kliewer and Stanley

Solomon.

1963--Nina became bedridden with

multiple sclerosis, her fist symptoms appearing in 1938, her

condition worsening by 1958.

1963--Became

Associate Professor of English.

1969--Became

Professor of English.

1973--Nina died on

October4.

1977--Ed retired from the University

of Kansas English Department with Professor Emeritus

status.

1977--Ed married Marguerite

Everett.

1978--Marguerite's daughter, Ed's

stepdaughter, Mildred Everett Villot, was slain in a Kansas City

hotel, in a murder that was never

solved.

1982--Ed diagnosed with

lymphoma.

1986--Published To All the Islands

Now, two long stories and a narrative essay, with Woodley Press

of Topeka.

1989--George Edgar Wolfe died in

Kansas City, Kansas, on April 20. His ashes were scattered on Fox

Ridge, next to Nina's, by his good friend Roy

Gridley.

Return to Top of Page

|

|

| Primary Documents |

| |

"Tom Averill on Edgar Wolfe" article, January 1984

"Teaching Experience Plus" by Edgar Wolfe

"Telling Stories" article by Edgar Wolfe, January 1983

Letter from Edgar Wolfe about his book "To All the Islands Now", October 1985

Heartland Bookletter 2 article "Ed Wolfe at 80", Jan. - Feb. 1987

Return to Top of Page |

|

|

| Links |

|

| |

A page created by Robert Lawson, of Washburn

University, to review Wolfe's book To All the Islands

Now.

Ordering information for To All the Islands

Now, from Woodley Press.

Read Widow Man on the Center for Kansas Studies website.

Return to Top of Page |

|

| |