Washburn UniversityCenter for Kansas Studies

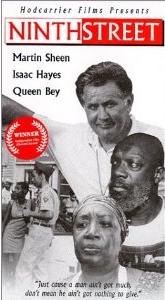

Ninth Street

Article Written by: Thomas Fox Averill

Ninth Street is a told story. The filmscript began as a play by Lawrence writer Kevin Willmott, who wanted to capture the place where he grew up, the Ninth Street where his own parents met. Bebo (Don Washington), a wino who watches over Ninth Street from a ratty sidewalk couch with his companion Huddie (Kevin Willmott) has the compelling voice. At the film's beginning, he tells the history of this one-block, black-owned center of sin, this haven for the 9th and 10th Cavalry, the Buffalo Soldiers, who would have nowhere else to go. Historic photographs of Ninth show a community cemented by music, dance, food and cards. Bebo, an admitted failure at nearly everything--marriage, work, sobriety--is disaffected that nothing changed for Blacks after World War II. He sees the Vietnam War as yet another enslavement: "Soldiers and whores are the same," he says. "In it for the money. The pimp's the U.S. Government."

Bebo and Huddie may be winos, but they stretch us with their smart "trash" talk: "Talking trash, talking shit. Keeps us from going mad." When someone asks them just what they're doing, Bebo says, "We're looking, is all. If God wanted everyone to live like us, we'd be the only successful ones." The moon landing foreshadows a lunar Siberia for Blacks, says Bebo, but he makes a simple toast: "To the white man who wants to go to the moon. May he stay there." And Bebo and Huddie feel sorry for the white man, always watching all his stuff: "You'd think he'd want to blink." The two are full of life, as is Ninth Street itself. "Just living gives you meaning," Bebo says towards the end of the film, and "there was life on Ninth Street."

There are also all the conflicts of life. In a religious sub-plot, Father Frank (Martin Sheen) is in trouble with his white parishioners for bringing his faith to the inhabitants of Ninth. He, too, is against the Vietnam War, and believes in a non-violent Jesus who befriended sinners. Another religious man, born-again Black preacher Johnny, advocates change. As Ninth Street changes, he says, simply, "The street is going to die. The wages of sin is death. Let it die."

But the street is life for its oldest denizens. Matriarch among them is Mama Butler (Queen Bey), whose joint is full of music, food, love and story-telling. She looks after a young prostitute, Carrie Mae (Nadine Griffith), who has a baby and has become involved in the power-hungry, thug-muscled gangster life of pimp Donnie Love (Byron Myrick). Love believes in nothing but "toughness." Mama is pushing Carrie Mae away from "the life" and from Love, since both are nothing but death. As Huddie tells pimp Love, "Boy, best find you something that doesn't die." In a climactic scene, Mama is gunned down by a soldier just returned from Vietnam, who pulls a gun on an oriental woman, gibbers in Vietnamese, then shoots Mama when she tries to disarm him." As Bebo says earlier in the film: "They know how to send them over there, but couldn't know what to do with them when they come back."

Over the protests of Bebo, Huddie and Tippytoe (Isaac Hayes)--the proprietor of a Ninth Street cab company--Donnie Love buys Mama Butler's place, and is ready to renovate it into a new kind of club. Carrie Mae has left "the life." Father Frank has been transferred for being where Jesus would have been--among the sinners. "Pop-bottle" Ruby (Kaycee Moore) has been carted away to Topeka State for destroying a television set she's taken from a business--her son disappeared in Vietnam, and she sees him on the television news. Just after Mama Butler's death, Bebo and Huddie sit on their couch eating the last of her bread, and drinking their wine. For their communion, they reminisce about the days when the Blues were king, were "about possibility." They remember 18th and Vine in Kansas City, and their own youths on Ninth, when they sported fine clothes and pomaded hair.

Their communion resurrects nothing but memory. Ninth Street will die, as does Huddie, on his couch, surrounded by a night of soldiers, drinkers, gamblers and prostitutes. In a final voice over, Bebo recounts his move to California, his drying out, his healthy life for twenty more years. Ninth Street has fallen victim to Urban Renewal. This once-vital community, the center of so much life, has became a parking lot.

Ninth Street resonates with the transitions faced by many Kansas communities. Towns are being de-populated, losing their vitality, seeing their oldest and best citizens die, floundering for lack of tradition, reminiscing about the richness of life they once embodied. Ninth Street faces this contemporary Kansas theme squarely, with wit, wisdom and real emotion. Written by a Kansan, and filmed here as well, Ninth Street is a solid addition to Kansas cultural studies.