Washburn UniversityCenter for Kansas Studies

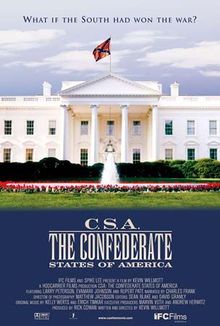

C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America

Article Written by: John C. Tibbetts

*Article used with permission from the Kansas Historical Society*

“Art is the lie that makes us realize the truth.”

— Pablo Picasso

“What if the South had won the Civil War?” That is the provocative question Lawrence filmmaker and University of Kansas assistant professor Kevin Willmott asks in his new “mockumentary,” C.S.A. Cast in the form of a documentary produced by the “The British Broadcasting System” and aired on Confederate television, it depicts a post-Civil War America dominated by a racist government, a “Confederate States of America.” The film’s imaginary chronology begins with the Confederacy’s victory over the Northern forces at Gettysburg in 1864; continues with the flight into Canadian exile of former president Abraham Lincoln and other Northern sympathizers; and touches upon other historical events leading up to the present day, including a “revisionist” examination of the circumstances leading up to Pearl Harbor, the “truth” about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, and the establishment in the Reagan era of the Family Values Act (an institutionalized form of racist entertainment programming). Threading its way through this historical progression is a storyline involving the rise to national political dominance over a 150-year period of a racist Southern family, the Fauntroys. And interspersed through it all are recreations of historical events, faked television commercials, staged media events, and on-camera interviews with two faux historians—a white southerner (Rupert Pate) and an African Canadian (EvaMarii Johnson).

Willmott’s “what if?” speculation joins a distinguished list of similar interrogations of the course of American post- Civil War history, notably Ward Moore’s novel Bring the Jubilee (1953), MacKinlay Kantor’s historical essay If the South Had Won the Civil War (1961), and Harry Turtledove’s The Guns of the South (1992). Such “counterfactuals,” as historian Niall Ferguson dubs them in his book Virtual History: Alternatives and Counterfactuals (1997), only recently have acquired intellectual respectability as a viable way of approaching that elusive truth known as “history.”6

Precedents on a broader level also are plentiful. In 1825 Thomas Babington Macaulay defined history as the locus of reason and imagination, between a map and a landscape. Anthologies such as John Collings Squires’s pioneering If It Had Happened Otherwise: Lapses into Imaginary History (1932), Daniel Snowman’s If I Had Been. . . Ten Historical Fantasies (1979), and Geoffrey Hawthorn’s Plausible Worlds: Possibility and Understanding in History and the Social Sciences (1991) have asked such questions as “What if Don John of Austria had married Mary Queen of Scots and the Reformation had never happened?”; “What if Napoleon had escaped across the Atlantic to America?” and “What if John Wilkes Booth’s Lincoln assassination had failed?”7 Sinclair Lewis’s novel It Can’t Happen Here (1937) postulated a Fascist takeover of America. And a cottage industry has grown around speculations concerning the Axis victory in World War II, including Noel Coward’s play Peace in Our Time (1948), Kevin Brownlow’s film It Happened Here (1965), and Philip K. Dick’s novel The Man in the High Castle (1962).

Ferguson suggests such speculations are not merely idle whimsies; imagining alternative histories can be a vital part of how we learn, opening up to the historian the basic method of the scientist by providing a means of testing hypotheses. Citing historian Isaiah Berlin’s critique of determinism, Ferguson says counterfactuals go wrong only when they provide implausible answers to improbable questions. “In short,” writes Ferguson,

by narrowing down the historical alternatives we consider to those which are plausible—and hence by replacing the enigma of ‘chance’ with the calculation of probabilities—we solve the dilemma of choosing between a single deterministic past and an unmanageably infinite number of possible pasts. The counterfactuals we need to construct are not mere fantasy: they are simulations based on calculations about the relative probability of plausible outcomes in a chaotic world.8

Plausibility and probability underpin some of C.S.A.’s more outrageous propositions. In a February 21, 2003, Lawrence Journal–World interview, Willmott revealed that he loosely based his outline for an American Confederacy on the fact that the Confederacy had indeed drawn up advance plans for a “Tropical Empire” after its presumed victory over the North. “They had an actual plan,” Willmott said. “So I used that as a blueprint—I didn’t make that up.” Lincoln’s flight in blackface and capture by Confederate soldiers—one of C.S.A.’s more amusing sequences— acquires a kind of authenticity because it is told by way of a convincing pastiche of a D.W. Griffith Biograph short (and we are reminded that, in real life, Jefferson Davis purportedly tried to avoid capture by fleeing south dressed as a woman). Another film pastiche, an excerpt from a faux biopic The Jefferson Davis Story, captures perfectly the look and manner of a 1940s Hollywood film.

The Confederate government’s use of tax abatements to induce the Northern population into taking up slave ownership recalls similar techniques with which our government currently entices big business into desired actions. The organization of the NAACP takes on a dreadful alternative existence as the National Organization for the Advancement of Chattel People. The exploitation of the Chinese immigrant population on the West Coast and the subsequent expansion by the C.S.A. south to Mexico and South America seem disturbingly rational, given the circumstances depicted. The reasons advanced for the C.S.A.’s participation in Kennedy’s assassination—his support of the abolition of slavery—remind us that, in real life, one of the many conspiracy theories in circulation contends that anti-civil rights factions in our own government frowned on Kennedy’s pro-civil rights stance and may have played a part in his assassination.

Even the television commercials interspersed throughout have the ring of truth. We might think, for example, that the ads for “Nigger Hair Tobacco,” “Darkie Toothpaste,” and the “Coon Chicken Inn” restaurant chain take Willmott’s parody too far, until the end credits inform us that such products actually existed! Another commercial depicts a Home Shopping Network-type program that specializes in marketing slaves (“today we have forty Negroes right off the tarmac, waiting for you!”). Most painful to watch, perhaps, is a commercial for “The Shackle,” a device useful in tracking down runaway slaves (“made of a lightweight aluminum alloy so it won’t weigh your Tom down; perfect for children”).

The not-so-subtle conclusion of this film is that yes, indeed, the South really did win the Civil War, and a deeply entrenched racism still exists today. “The South may have lost on the battlefield,” argues Willmott, “but it won the fight for ideology. Look at Lawrence, a town founded on abolition but which later turned to segregation.” This is the racism that, in many quarters, still contends that “states’ rights,” not slavery, was the key issue in the Civil War.9 As Willmott argues: “There are a lot of people today who want to divorce slavery from their Southern heritage. My film restores slavery as the centerpiece of that conflict.”

Willmott began working on C.S.A. in 1997, while finishing up a previous project, Ninth Street (reviewed in the summer 2001 issue of Kansas History). By dint of a PBS-affiliated grant from the National Black Program Consortium, the assistance of cinematographer Matt Jacobson (also a professor in the University of Kansas film studies program), and the cooperation of many students, colleagues, and professional Kansas City actors, he has persevered through five years of changes and revisions. The film received its premiere at a benefit screening at Lawrence’s Liberty Hall on February 21, 2003.

John C. Tibbetts

Kansas University

(John C. Tibbetts wishes to acknowledge the assistance of

Mark von Schlemmer in the preparation of this article.)

6. Niall Ferguson, ed., Virtual History: Alternatives and Counterfactuals

(London: Papermac, 1998).

7. Simon Schama, “Clio at the Multiplex,” New Yorker (January 19,

1998): 40; John Collings Squires, If It Had Happened Otherwise: Lapses into

Imaginary History (New York : Longmans, Green, 1931); Daniel Snowman,

ed., If I Had Been . . . Ten Historical Fantasies (Totowa, N.J.: Rowman and

Littlefield, 1979); Geoffrey Hawthorn, Plausible Worlds: Possibility and Un-

derstanding in History and the Social Sciences (New York: Cambridge University

Press, 1991).

8. Ferguson, Virtual History, 84–85.

9. For the most recent instance of this claim, see the Ted Turner-produced

Gods and Generals (2003).