----------

----------

Gene DeGruson---------Goat's House

My Kansas author for November, 2005, is again Gene DeGruson. The theme for the Kansas Authors' Club Contest this year was: Southeast Kansas: Who Walked These Trails. So I wrote both a poem and an essay on Gene DeGruson, who was one of my best friends among Kansas writers--and the best from Southeast Kansas. I did not win with either, but it brought Gene strongly back to mind, which leads me to feature him again as my Kansas author of the month. I will include the poem I wrote, "Camp 50," here, and both poem and prose article, "Gene DeGruson--Poet Laureate of the Little Balkans," with my earlier item on Gene (April-May, 2002), which includes the complete text of his book of poetry, Goat's House, published by the Woodley Press in 1986, but out of print for years.

----------

----------

Gene DeGruson---------Goat's House

A special book of poems,CAMP 50

Goat's House, by Gene DeGruson,

Presents a whole cast of characters

Who once walked the trails

Of Southeast Kansas.As in the one-of-a-kind journalEven within the family there were aliens.

He edited in the '80s,

The Little Balkans Review,

It is that sub-region he emphasizes,

And, still more specifically,

He tells stories he's heard since he was a boy

Growing up in Camp 50

A coal-mining town near Arma

Where, early in the century,

The miners were all immigrants--

But from across Europe--aliens from each other.

Both of Gene's grandfathers were miners from France,

And, following them, his father died of black lung disease.

A dying grandmother,

Who had "stubbornly resisted

the language until refusal became habit,"

Might speak in "a secret tongue I could not share,"

Trying to reach a puzzled grandson,

Giving him "strange gifts,"

A "Tricolored ribbon, a centime piece."Some are reported stories of the old daysAnd the values of these men and women of Camp 50

When Alexander Howat led the union attacks

Against the scabs, and "In '21,

[Gene's] mother . . . at seventeen

marched for Alexander Howat to bust the scabs

who worked the mines in place of the fathers."

Shaped the life of this poet,

Who became a distinguished professional historian

Of Southeast Kansas at Pittsburgh State University,

And who gathered these stories

Of those who had walked the trails

Of Southeast Kansas, at Camp 50,

While walking those trails himself.

No one could be more the product of Southeast Kansas than Eugene Henry

DeGruson. Born in Girard October 10, 1932, he died of a cerebral

aneurysm on June 18, 1997, at age 64, in a hospital in Joplin, Missouri,

and, as Charles Cagle tells us, "is buried in Union Cemetery, a quiet country

place northwest of Pittsburg."1 He

reached out from that center in many ways, but certainly Pittsburg State

University became the center of his life.

He was born of French immigrants to Southeast Kansas on both sides.

His father, Henry DeGruson came from France as a one-year-old boy with

his father, a French coal miner who found work as a coal miner in Kansas.

However, "His wife refused to leave France. He returned three times

before she would consent to come, and she refused to learn the language.

By that time, 1912, the boy, not yet 10, had crossed the ocean five times."2

This son, Gene's father, also became a coal miner. Gene's mother

was Clemence Merciez, whose father was also a French immigrant and coal

miner, and whose own mother never learned to speak English, either, which

adds a poignancy to the title poem of Gene's book of poetry, Goat's

House.

Thus, the son and grandson of coal miners, he grew up in Camp 50, a coal

mining community just west of Arma in Crawford County, and on a farm near

Weir. He graduated from Crawford County Community High School in

Arma, then Pittsburg State University, where he earned two degrees, B.S.Ed

(1954) and M.S. in English (1958). He did graduate work in bibliography

at the University of Iowa (1958-60, 1963-64). He taught at Highland

Park High School in Topeka (1953-57) and was active in Topeka Civic Theatre,

where he had the lead in Teahouse of the August Moon.

After he returned to Pittsburg, he continued to be active in theatre, both

as director and actor, translating Moliere's The Doctor in Spite

of Himself for the Tent-by-the-Lake Theatre and then playing the

lead in 1961, for example.

He came home to join the Pittsburg State University faculty as instructor

in English in 1960, when his father was dying of black lung disease.

Then in 1968 he became a professional historian, when asked to become Special

Collections Librarian for Southeast Kansas materials at the Leonard H.

Axe Library at PSU, a position created for him, at first, "to catalog the

papers of Emanuel Haldeman-Julius, a radical Girard publisher. . . . a

pioneer, the first to see the promise of paperbacks, [whose] Little Blue

Books--5-cent, throwaway editions of the classics--became famous."3

This turned out to be quite a project, one thing leading to another as

Gene used his special interest in his region and his position as librarian

in tracking, recording, and preserving the history of the area and state

most of his life, until he became known as the most knowledgeable historian

on Southeast Kansas, his collection a center for research on the region.

In 1981 he was appointed University Archivist. Later, after a fantastic

find of early papers of the important socialist magazine the Appeal

to Reason (published in Girard), which had serialized the first

edition of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle, he engaged

in the laborious project of reconstructing that work (he tells the story

in the introduction) , which finally led to the publication of his

"The Lost First Edition."4

It was as a regional historian, and based on some of the editorial and

bibliographical work that came out of that that he was best known professionally.

Again building on this regional base, one of his most distinguished literary

achievements was as the editor, and particularly the poetry editor, of

The Little Balkans Review (which used his home address as

address) for nine years, 1980-89 (The Christian Science Monitor

called it one of the three best regional magazines in the country).

The cover of the first issue, in the fall of 1980, featured Independence

native, playwright William Inge, and the emphasis was always on Kansas,

and particularly Southeast Kansas, authors.

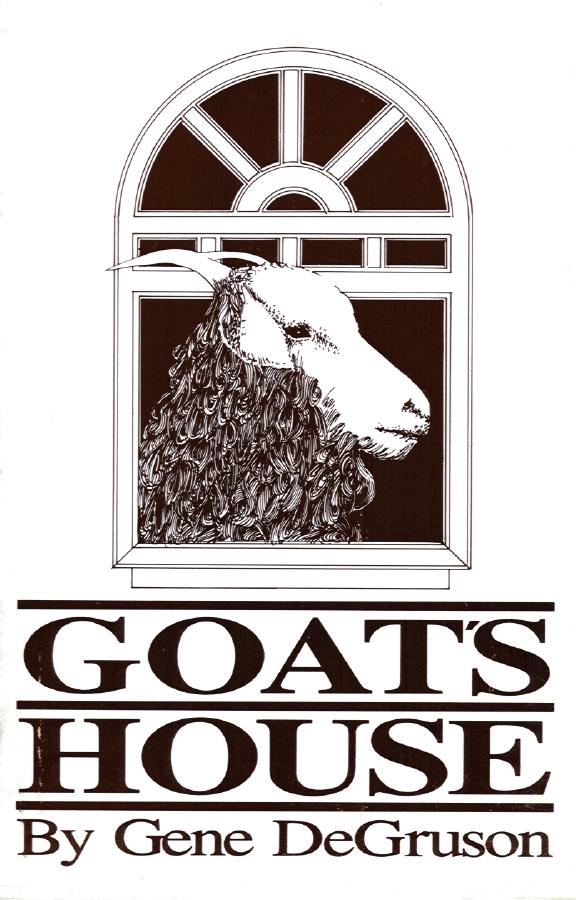

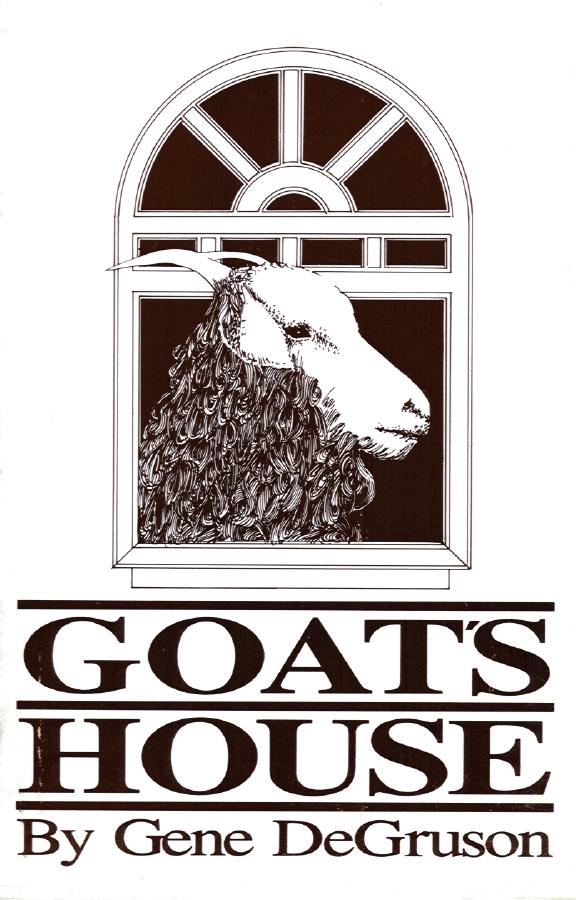

But it is as a poet of Southeast Kansas that I would like to emphasize

his achievement. In 1986, Gene won the first Robert E. Gross Memorial

manuscript competition sponsored by the Woodley Press, at Washburn University

in Topeka, with a book of poems. That volume, Goat's House,

is a special tour of one man's memories, of the stories he heard growing

up and the people he grew up among, captured by the imagination of a writer

who recreated their idiom, their humor, their sorrow and hard times, their

joys, their eccentricities. A printing of 500 was soon sold out and

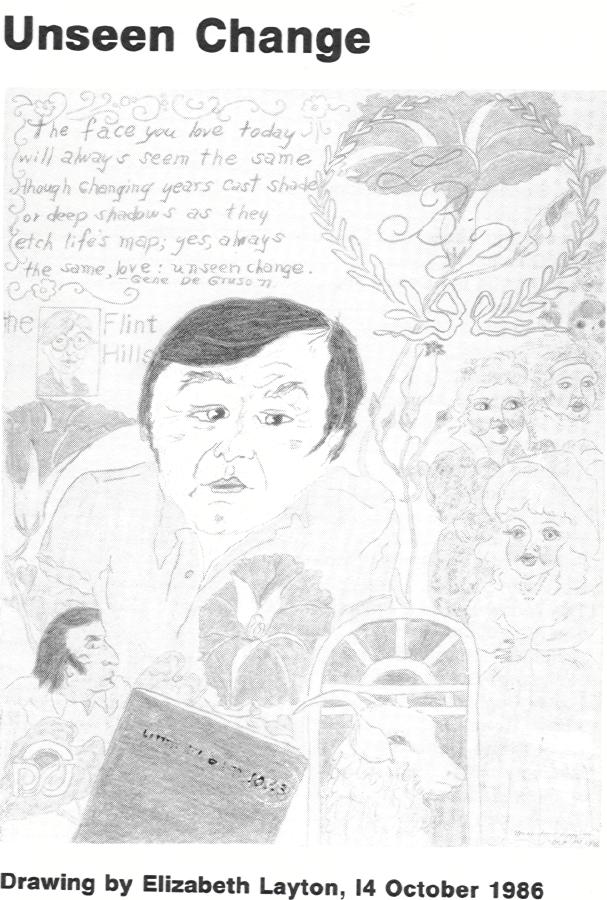

a second printing added seven more poems (and a picture of Gene drawn by

Grandma Layton, who had become a good friend, which was used as frontispiece).

That second edition, too, soon sold out, so the book has been out of print

for years (but is now available below5).

Goat's House, as Denise Low describes it in her introduction,

is unified in its subject matter: "Basic to virtually all his work is an

impulse to save the past . . . of Southeast Kansas, the 'Little Balkans'

of myriad nationalities. This mining area also provides the context

for the poems in this volume. Unlike much recent contemporary poetry,

DeGruson's work is narrative rather than lyric; he relates stories, not

his own musings. And these stories revolve around his community,

from the labor leader Alexander Howat to an anonymous Polish immigrant.

. . . Goat's House includes stories from DeGruson's own rich

past as well as those from the past of the region. . . . DeGruson recounts

numberless anecdotes about common folk who contributed to the Little Balkans

in their own ways. In addition, he restores to our collective memory

the national history made during mining days and during the formation of

labor unions."6

The poetry in the book is divided into three sections (with all but two

of the thirty-three poems dedicated each to a different friend, mostly

from Southeastern Kansas):

I. STILL AN ALIEN

The first section presents Gene's own memories as a boy in Camp 50, surrounded by people, including family, who were new immigrants, of many races, so some very strange characters, from the gypsies who frighten his mother, for fear they'll steal her child, in the first poem, to Felix Janeskie, the Polish bachelor whose phrenological drawings of his neighbors and other peculiar habits no one understood, to Old Lady Bob who, after a first failure ("broke both legs"), still thought she could fly, to Theresa, the woman of many affairs, who, now 71, has memories of the past, when "Sicilian deceit was sweet." The title poem explains both the title of the book and the sub-title of this section, and offers a perceptive picture of a boy's puzzled relationship to his dying grandmother:

So many women did not want to come here,Goat's House

including my grandmother, who loved France.

It was stark then, the landscape, without trees,

smogged by smelters which promoters called

prosperity. Although timid, she stubbornly

resisted the language until refusal became a habit.Thus there was always a translator present

When she talked to those of us born in the new country.

You could tell from her eyes that something was lost,

but we impatiently hurried off to play

when her questions or comments didn't make sense,

irrelevant, like going to the goat's house for wool.On her deathbed she gave me things and crooned

their mysteries in a secret tongue I could not share:

a Tricolored ribbon, a centime piece, a celluloid

doll that drank from a bottle with a long, long

tube which ran to the nipple: strange gifts

for a child who did not know why she gave.

II. HOMAGE TO ALEXANDER

HOWAT

The second section is more historical, gathering stories told by older residents of Camp 50 about the old days in the mines, focusing on the union activity in the coal mines, with stories by those who had marched with Howat, the union organizer, and attacked the scabs: ("The first scab to come out of the air shaft was the superintendent, the first of forty-two men to get whipped that day.") Then other stories of cave-ins, deaths in the mine and the lives of widows. But there is also an underlying humor, as in the fighting over "the left hind foot of a graveyard rabbit" in "Hometown Burial," and irony, as in the portrait of Agnes Howat, presented as her husband remembered her. The most personal touch in this section would seem to be in "Alien Women" (dedicated to Clemence Merciez DeGruson, his mother). Its first stanza reads:

Alien Women

In '21, my mother still herself

at seventeen marched for Alexander

Howat to bust the scabs who worked

the mines in place of the fathers

and husbands of the thousand women

who marched with her carrying

their men's pit buckets filled

with red pepper to throw in the eyes

of the poor scabs who cursed back

in English to their Slovene, German,

French, and Italian over

the State Militia's rifle fire.

Gene still lived with his mother, and the second stanza tells how "It's

all dim in her mind now." She doesn’t remember what a force that

"Army of Amazons" was.

III. A STONE DOORSTEP

The third section is more general, from warning "the unsuspecting bride" against planting trumpet vines to a fantastic description of "The Garden of Eden" in Lucas, Kansas (dedicated to Elizabeth Layton, this and the last poem, "Clark County Digression," probably the only two not set in Southeast Kansas). These poems are more various, but the characters still mostly unusual people who caught Gene's imagination. The one I like best is:

I think of Gene's house, which he called "The Castle," in its museum quality, as epitomizing his interest in the exotic in Southeast Kansas. It was unique, "a 57-year-old concrete castle with a corrugated steel 'umbrella' on top . . . designed and built by one of Pittsburg's most remarkable characters, lawyer A. Staneart Graham. . . . He built his house with railroad rails for structural supports, and debris of all sorts for the rest."7 Gene loved that house, and collected things there. He was on the Woodley Press board of directors the last few years of his life, and they came to schedule summer meetings there, car-pooling the 200 miles routinely for the pleasure of having Gene as host, and guide through that museum of Southeast Kansas.It was illogicalThe Stranger in Her Room

that she should enter her own house

to find him, a stranger, sitting in the dark.

But there had been such a sunset

he wandered in to use a window,

turned off the lamp to watch the sky,

and when it died he watched it still,

not hearing her steps, not realizing

her incomprehension of his sitting in the dark,

a smiling stranger, whose privacy

had been invaded.

General Note: I am particularly indebted for factual information to two articles by Zula Bennington Greene (Peggy of the Flint Hills), Gene's good friend from his Topeka Civic Theater years until her death (to whom he dedicated Goat's House), published in The Topeka Capital-Journal, Thursday, August 28, 1986, when the book was first published, and then Tuesday, January 20, 1987, when a second edition was printed, and, more particularly, an excellent, fact filled, article by Gene's friend and colleague, Charles Cagle, published in The Pittsburg State University Magazine, Fall, 1997, shortly after Gene's death. pp. 8-10, 16.1Charles Cagle, "A Lost Treasure," Pittsburg State University Magazine, Fall, 1997, p. 8.

2Zula Bennington Greene, "Peggy of the Flint Hills," The Topeka Capital Journal, August 28, 1986.

3Adam Rome, "For the Love of Kansas," The Wichita Eagle-Beacon, Sunday, September 27, 1987.

4Gene DeGruson, The Lost First Edition of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle (Peachtree Press: Atlanta,

Georgia, 1988), pp. xiii-xxxi.

5http://www.washburn.edu/reference/bridge24/DeGruson.html.

6Denise Low, "Introduction," Goat's House (Woodley Press, Washburn University, Topeka, 1986), p. ix.

7Rome

8Cagle, 10

9Cagle, 8

Gene DeGruson's Goat's

House

Gene Degruson's book of poems, Goat's House, was published by The Woodley Press in 1986, but had already been out print for years (after selling out two printings) when Gene died June 18, 1997. He was a very special friend to The Woodley Press, was on the Board of Directors for years, and we sometimes met at his unique home in Pittsburg, Kansas. He had published many other things, particularly The Little Balkans Review, which he edited for years, and an acclaimed edition of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle based on special research. And, a good friend of Elizabeth Layton, he was working on a collection of her poetry, which the press was to have published. But he did not have a book of poems, plays, or stories in print, so I have not featured him as one of my "book in print" Kansas authors here on my web site.

Since I am modifying my own guidelines this year, however, I decided not only to feature Gene for April, with three of the poems and Denise Low's Introduction, but, with the consent of his family, now, in May, present the whole text of Goat's House, for which we get frequent requests, so it will be available again--at least on the internet. Here it is:

_____ ______

______

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author

is indebted to Charles Fedell, Marjory Graflin, Thomas Bunskill, Frank

Caput, Vance Randolph, Mary Molek, and Margaret E. Haughawout, among others,

for folkloristic and historical elements utilized in these poems, as well

as to articles from the Girard Press, Pittsburg Headlight,

Kansas

City Star, and the Appeal to Reason. Mary Heaton

Vorse is quoted in "King of the Miners," p. 31.

Special thanks

must be extended to Charles H. Cagle, Charles W. Dobbins, Al Ortolani,

Jr., Stephen Meats, and Virginia Laas for reading portions of the work-in-progress,

and to my editors, Cynthia Pederson, Celia Daniels, and Denise Low.

It was Bill Dobbins who brought to my attention the proverb used by Miss

Mary Allen in her high school classroom in Arcadia, Kansas, when she could

not answer a student's question: "You've come to the goat's house for wool."

I should not

omit from these thanks my mother, who always took a curious child with

her

on visits to friends and relatives throughout the region known as the Little

Balkans of Kansas and who has shared with him her thoughts and memories

over the years.

Certain of

these poems appeared earlier in Bitterroot (Menke Katz, editor),

Crazy

Horse (Philip Dacy, editor), Kansas Quarterly (W.R.

Moses and Harold Schneider, poetry editors), Little Balkans Review

(Gene DeGruson, poetry editor), Midwest Quarterly (Rebecca

Patterson and Michael Heffernan, the consecutive poetry editors),

Ozark

Mountaineer (Edsel Ford, poetry editor) and South and West

(Sue Abbot Boyd, editor). I am appreciative of their help and encouragement.

"Dog Days in the Coal Camp" and "Shoes, Egg Shells, and Carefully Labeled

Heads" appeared earlier in Confluence: Contemporary Kansas Poetry,

edited by Denise Low (Lawrence, Kan.: Cottonwood Press, 1983).

This volume

was designed by Martin J. Graham of Washburn University, printed by Hawley

Printing and bound by Western Bindery of Topeka, Kansas.

This revised

second printing of 500 copies is supplemented with new poems and a drawing

by Elizabeth Layton of Wellsville, Kansas, typeset by the author on 9 November

1986 at Words and Pictures in Triumvirate Regular, with titles in Triumvirate

Heavy, and published by the Woodley Memorial Press of Washburn University

Topeka, Kansas 66621, Robert N. Lawson, editor.

The cover

design is by Rod Dutton of Words and Pictures, Inc., Pittsburg, Kansas.

The portrait of Gene DeGruson on page [54] is by Ted Watts, of the Ted

Watts Art Studio, Oswego, Kansas.

Copyright © 1986 by Gene DeGruson. All rights reserved.

FIRST EDITION, SECOND REVISED PRINTING

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

ISBN 0-939391-06-6

THE ROBERT E. GROSS

MEMORIAL

MANUSCRIPT COMPETITION

In the fall of 1985, the

Robert E. Gross Memorial Manuscript Competition was established.

This competition was designed not only to encourage those writing poetry

and to provide an avenue for publication, but also to promote poetry statewide.

With prize money donated by Karen Roth, wife of the late Robert Gross,

this competition was named in honor of this graduate of Washburn University.

Robert Gross attended Washburn from 1977 to 1980, during which time he

was active as a member of Headwaters Writers Organization and served as

well as an editor of four issues of Inscape. His publications

include fiction and poetry in Inscape and 30 Kansas

Poets. Mr. Gross was graduated cum laude in the summer of

1980 and left soon after to live and write in California. He died

on October 6, 1984, in San Francisco.

For Robert Gross, as for

many of us, the struggle toward establishing a reputation as a writer and

pursuing publication proved to be a frustrating experience. From

across the state of Kansas, the many submissions to this competition reflected

this struggling spirit and a sense of perseverance. This winning

volume is dedicated, in part, to the memory and spirit of Robert E. Gross.

Cynthia S. Pederson

Manuscript Editor

This volume is dedicated

with love, respect, and admiration

to Zula Bennington Greene.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Unseen Change, drawn by Elizabeth Layton | viii |

| Introduction, by Denise Low | ix |

| I. Still an Alien | |

| The Gypsies | 5 |

| The Biggest Kite in the World | 6 |

| First Flight | 8 |

| Shoes, Egg Shells, and Carefully Labeled Heads | 9 |

| The Dream | 10 |

| Dog Days in the Coal Camp | 11 |

| The Funeral | 12 |

| The Franklin Faith Healer | 13 |

| Goat's House | 14 |

| Theresa | 15 |

| II. Homage to Alexander Howat | |

| The March on Cherokee | 21 |

| Alien Women | 22 |

| After the Cave-In | 23 |

| The Worrier | 24 |

| Found Poems | 25 |

| Widow's Income | 26 |

| Frank Caput Remembers Howat | 27 |

| No Prize | 28 |

| The Widow Makes a Statement | 29 |

| The King of the Miners | 31 |

| Deserted Homestead | 32 |

| Hometown Burial | 33 |

| Highly Sophisticated Swedes | 34 |

| Agnes Howat | 35 |

| III. A Stone Doorstep | |

| Warning | 41 |

| Another Landscape | 42 |

| The Garden of Eden | 43 |

| Catfish Legacy | 45 |

| The Stranger in Her Room | 46 |

| The Visit | 47 |

| Miss Haughawout Remembers E. Haldeman-Julius | 48 |

| Mockingbirds and Saloons | 49 |

| The Policeman | 51 |

| Mother Jones | 52 |

| Clark County Digression | 53 |

INTRODUCTION

Gene

DeGruson long has been respected in the Midwest as a publisher and editor

of The Little Balkans Review and as an active librarian,

but most of all as an historian. Basic to virtually all his work

is an impulse to save the past. The Little Balkans Review,

for example, in addition to publishing contemporary literature, has been

a vehicle for uncovering the background of Southeast Kansas, the "Little

Balkans" of myriad nationalities. This mining area also provides

the context for the poems in this volume.

Unlike

much recent contemporary poetry, DeGruson's work is narrative rather than

lyric; he relates stories, not his own musings. And these stories

revolve around his community, from the labor leader Alexander Howat to

an anonymous Polish immigrant. His chronicles always sustain our

interest, either by focusing on one person or by quoting or even by relating

incidents from newspapers ("found" poems).

Goat's

House includes stories from DeGruson's own rich past as well as

those from the past of this region. The title poem, in fact, is derived

from a Balkans saying: "You've come to the goat's house for wool."

This proverb responds to a question to which a speaker has no immediate

answer. However, a reader has not "come to the goat's house for wool"

in opening this book. DeGruson recounts numberless anecdotes about

common folk who contributed to the Little Balkans in their own ways.

In addition, he restores to our collective memory the national history

made during mining days and during the formation of labor unions.

And

in the telling, the narrator reveals himself. He uses a rich language

for the history that he loves so well. The poems pass on bits of

wisdom; so many of them read like parables. The narrator's involvement

in many diverse cultures--French, Swede, Italian, Eastern European--leads

to tolerance and celebration of humankind.

DeGruson's

intrigue with history began with curiosity about his French grandmother:

On her deathbed she gave me things and croonedYears later, as an adult, Gene DeGruson has embellished this exotic inheritance. By adding to this child's collection, he shows that he has come a long way towards understanding his grandmother's gifts. And he offers this collection to us.

their mysteries in a secret tongue I could not share:

a Tricolored ribbon, a centime piece, a celluloid

doll that drank from a bottle with a long, long

tube which ran to the nipple: strange gifts

for a child who did not know why she gave.

Denise Low

Lawrence, 1986

I. STILL AN ALIEN

"This place, then, this Kansas, with its rich ethnic mix, its political tumult, and its flavors of the old western frontier, was home to [Vance] Randolph for the first twenty years of his life. There's a sense, too, in spite of the long Ozark residence, in which he never left. In 1946, for example, . . . he writes to his closest Pittsburg friend, Ralph Church: 'There comes a time when a man needs to be with people of his own kind. I like these Ozarkers better than any people I ever knew, but after all they are not my people. Despite the twenty-five years I have spent here, I am still an alien'."--Robert Cochran, Vance Randolph: An Ozark Life (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1985), p. 20.

THE GYPSIES

For Bess Spiva TimmonsTheir wagons clambered into view

so suddenly I had no time when Mama

cried to hide or come inside

so I crowded among the lilacs

with her tales of stolen childrenwhile she feared the slight

whiskered man and ear-ringed women

in careless colors who smiled their way

up to our house in the fading sunlight

and cajoled. For what she didn't knowsince her son was beyond her in the lilacs,

her husband working night shift at the mines,

and behind her was the unlocked kitchen door,

unwatched, except possible by those

who crept to try its knob.They left. She made my eight years

sleep with her that night, waking me

with her paralyzed No No No

as her dream fortune was smilingly told

and their wagons left, bulging with lilacs.5

THE BIGGEST KITE

IN THE WORLD

For Charles CagleA young buck heard about the kite

and decided to build a bigger one

right there in Chicopee.

And he did.

But before letting the world know about it,

he and his buddies decided

they'd better try it out first.

It flew all right, but they didn't know

if flying the biggest kite in the world

was enough to impress their elders

who might scoff at such a damned fool thing.

So one cub suggested

The attention-getting added excitement

of affixing explosives to the tail--

which was no problem for kids

in a coal mining camp: it was done.

The added weight was compensated for,

but barely

had the kite

with three sticks of dynamite

hovered into the sky

than it swerved downward.

The boys ran,

pulling it hard across the tracks

and (before they realized it)

past St. Barbara's Church among the shacks

where old women cursed them

to get the goddamned thing out.6 And, of course, it landed

on a house.

Someone

had the presence

to give the rope a tug

before it blew, but a six-foot hole

in the street and broken windows

all over town

reinforced old wives' views

that people

just don't keep an eye

on their kids anymore

while the town's few old men

rumbled expletives

that are better not mentioned

in present company.7

FIRST FLIGHT

For Mary Goble Kennedy"I can only record pity for any of you who got through childhood without exposure to that rocket of the stars known as the Giant Strides. What it was--and you don't have to take my word for it--was 'a revolving disk attached horizontally to the top of a pole, with pendent ropes, holding to one end of which it is possible to take strides or leaps of thirty feet or more.' As I knew the Giant Strides (at Lowell Elementary, where they later raised chickens and now store hay), it had chains instead of ropes, each ending in a stirrup-like iron grip which was too hot to handle in the summer and too cold to hold in the winter, but which could raise a mighty wale on your noggin in any season."

--Edsel FordSuch jubilation when the school board

bought the Giant Strides, despite the fact

that Eldor' Ann broke her arm on the first

trial run: although as large as us,

she was much too small to cause

such great alarm when fun and newness

were the thing, though dangerous.

Forgotten were her arm, run sheepy run,

the bats, the ball, and whose turn first:

of only care were six chained handles

that hurled six of us in turns beyond

the district school house, classes, home,

into a sky where stifled breath and dizziness

of heart were all wee knew of earthliness

and all wheee cared to know. . . .8

SHOES, EGG SHELLS, AND

CAREFULLY LABELED HEADS

For Shelby HornFelix Janeskie, the Bachelor, was as much a hermit

as life would permit. He papered his walls with covers

of poultry magazines; he had known a woman once,

according to Marie Pernot, who asked; he could be

counted upon to have the latest Sears & Roebuck

catalog. When he died, each room of his shack

overflowed with shoes, egg shells, and catalogs

stuffed with phrenological drawings--chart after chart

labored in Polish: the physiognomies of each neighbor

blocked off into realms concealed from us by hair--

a mad, mystical, meaningless mess which was shoveled

into a well, capped clean, his house demolished, the land

leveled. Soy beans grow over the Bachelor's lot, save

for one corner, rife with weeds, which would destroy

any plow that scraped into the well cap waiting there.9

THE DREAM

For RosaleaOne dream he never wished to shelter

always returned to him: the child would

shinny the kitchen fence to visit the Polish

bachelor who papered his walls with covers

of poultry magazines. Vivid and glossy hens,

lithographed leghorns, brahmas, dorkings

and plymouth rocks, orpingtons

and wyandottes unblinkingly watched

the child until the dream would come.A large red smiling hen would chase

the boy for storybook miles until

on an untreacherous seeming hill he

neared his blackboard, flat upon the grass,

attracting him as a magnet thin strands

of steel, holding him, trembling

gently, to receive the beak. Awake,

his tears would not reveal the dream

that always came again, untildreams later

in shorn fields of Kaffir corn

dilating fears invaded daylight

when awakening

could not be

when claw thin furrows

etched his cheek

which everyone

could see.10

DOG DAYS IN THE COAL CAMP

For Robertson StrawnOld Lady Bob received from the Mouth of God

the revelation that she was to have the gift of flight.

She told everyone, hitching up her drab haying skirt,

and to all who stayed to listen she scheduled her flight

for the third next Sunday from the Polk School steeple.

Even skeptics--who were legion--came to see the show--

to the shame of a niece who begged Old Lady Bob

to stay firm on the ground, not to risk her neck,

but Old Lady Bob climbed and leaped, flailed

the air, and broke both legs. That's all. Old Man

Brunskill hollered, "What happened to your faith?"

as they took her inside to wait for the doctor.

"My faith," she answered back, "was strong. I

just got off on the wrong flop!" There was

no laughter--just the nagging thought, a pervasive fear,

she might try it again come dog days next year.11

THE FUNERAL

For Janis DeChicchioJust large enough to fill anybody's world

Mrs. Gillenwater snagged her coat on a rosebush

her son Floyd had filled with song the night

before and unknowingly dragged the shrub

to the funeral home, where Mrs. Mallams

still composed, her music drowning

out her neighbors' obsequies.

The rosebush fought back, sprouting

Floyd's love songs, and the choir

joined in, forgetting standard hymns,

until the pallbearers remembered duty,

stilled the sound, closed the lid,

and bore Mrs. Mallams to her grave.

Mr. G. innocently followed,

trailing seven sisters in full bloom

which attracted intermittent honeybees

and pesistent butterflies, which the preacher's

wife roundly condemned as ostentation.12

THE FRANKLIN FAITH HEALER

For Vivian BuchanShe healed many, her neighbors swear,

through her hands, through her prayers.She entranced eventually the disbelieving

who reluctantly had brought to her their grieving.A man struck by lightning she stripped,

rubbed red, and he rose from her bedfreed for the moment from the taint

of death. He was handsome in his praise.She recited his testimony while inching

health into other bodies; clinching fistsrelaxed, female pains, goiters, weakness

of the lungs calmed under the firmnessof her hands clean as chalk bottles, clean

as her kitchen floors, her weedless garden,clean as their talk when they spoke of her,

but none realizes she never smiled. Never.13

GOAT'S HOUSE

For Eva JessyeSo many women did not want to come here,

including my grandmother, who loved France.

It was stark then, the landscape, without trees,

smogged by smelters which promoters called

prosperity. Although timid, she stubbornly

resisted the language until refusal became habit.Thus there was always a translator present

when she talked to those of us born in the new country.

You could tell from her eyes that something was lost,

but we impatiently hurried off to play

when her questions or comments didn't make sense,

irrelevant, like going to the goat's house for wool.On her deathbed she gave me things and crooned

their mysteries in a secret tongue I could not share:

a Tricolored ribbon, a centime piece, a celluloid

doll that drank from a bottle with a long, long

tube which ran to the nipple: strange gifts

for a child who did not know why she gave.14

THERESA

For Rod DuttonMrs. Angelo Tocetti, the last important female

in Chicopee, answers my beery good-bye

to someone else, smiles, and fails visibly.

What leisured love that woman whetted

when Sicilian deceit was sweet, we've heard.

But now, at 71, her last commonlaw honeymoon

over, her tired secrets public knowledge, nightly

she learns--and forgets--"Who is to blame?"

suffices no longer. Oh yesterday.Tomorrow, maybe, will come in the boy

whose beer can smooth those wrinkles and

that voice, mask her stale musk of garlic.

Already tickling his palm, she mutters as she sips,

thin conflagrations flickering in the snow.15

II. HOMAGE

TO

ALEXANDER HOWAT". . . There are no shaft mines left in Southeast Kansas, but through the man we met, I felt as if I had experienced what life must have been like for him and his fellow workers and their families. I understood the strikes for more pay and better working conditions and the march of the Amazon Army (a miners' wives' protest); I wondered why I had never recognized this version of 'Bleeding Kansas.' People here did not bleed only over the issue of slavery, they bled in the mine fields and in the zinc and lead smelting plants. The very soil of Kansas bled with the extraction of coal. . . ."--Mil Penner and Carol Schmidt, Kansas Journeys (Inman, Kan.: Sounds of Kansas, 1985), p. 75.19 THE MARCH ON CHEROKEE

An Interview with Frank Caput

For Gabriel NaccaratoSheriff Jim Hyman met us

at the community store in Franklin

(we were marching with Howat

on the Simion mine in Cherokee).

He told us to avoid Pittsburg

and Girard, to go by South Radley.

There were fifty or sixty cars of us,

five or six men in each car,

the lead car flying an American flag.

The first scab to come out of the air shaft

was the superintendent, the first

of forty-two men to get whipped that day.

Secretary Harry Burg sang out

"Don't touch the boys!"

They were under age, you see, doing

what their fathers had told them.

So each time a kid come out

Henry would yell, "Open ranks,"

and the boys were allowed through.

But boy oh boy the other ones!21

ALIEN WOMEN

For Clemence Merciez DeGrusonIn '21, my mother still herself

at seventeen marched for Alexander

Howat to bust the scabs who worked

the mines in place of the fathers

and husbands of the thousand women

who marched with her carrying

their men's pit buckets filled

with red pepper to throw in the eyes

of the poor scabs who cursed back

in English to their Slovene, German,

French, and Italian over

the State Militia's rifle fire.It's all dim in her mind now. She

remembers only that she was hungry

and frightened. She does not remember

Judge Curran, who said, "It is a fact

that there are bolsheviki, communists,

and anarchists among the alien women

of this community. It was the lawlessness

of these women which made necessary

the stationing of the State Militia

in our county for two months

to preserve law and order."

She does not remember they

were called an Army of Amazons.22

AFTER THE CAVE-IN

For Barbara LaSalleThe great loneliness he promised her,

but which she knew would never come,

has come. . . . She is its city,

her avenues posted

with new standards of desire,

her limits expanded

beyond hope.A silent city.

She cannot

adjust to this numbness

in the voice of things: everything

muted, disembodied from source, even

the summer bees not yet divorced

from autumn fields.

Confidence

tatters in silence.

Everything scuds by unnoticed

as she idly touches each grain of salt

she spilled upon the table cloth.23

THE WORRIER

For Denise LowSelina--whenever trouble

came--would say in her

worried voice, "Boy, boy,"

quietly, the vowels lengthened

according to the seriousness

of the situation, her hands

quiet in her apron, all movement

in her voice: "Boy, boy."For hours Selina would gossip

over handleless cups about

old times in the old country,

but even in the summary security

of her kitchen on a Sunday

afternoon, from the porch

could be heard Selina's

"Boy, boy."24

FOUND POEMS

(The Girard Press, 4 May 1905)

1.

On the 2d, Laura Heath, of Pittsburg,

aged 27 years, was examined

by Drs. E.G. Cole and L.P. Adamson

and adjudged insane, the supposed cause

being an immoral life.2.

Last Sunday afternoon quite a number of Girard people

visited the county poor farm. Among others were

Mr. and Mrs. Henry Decker and children,

Mr. and Mrs. J.H. McCoy, Mrs. Minnie Kosper

and daughter, Mrs. W.F. Higgie, Mrs. J.L. Wheat,

Miss Mamie Buesch, and Mrs. and Mrs. E.A. Wasser.

Mr. and Mrs. Adsit made it pleasant for all.3.

Joe Rondelli, an Italian miner,

was crushed to death in mine No. 6

of the Mount Carmel Coal Co.

at Frontenac Tuesday afternoon,

a mass of slate and rock falling on him.

He left a wife and children.25

WIDOW'S INCOME

For Bonnie MartinShe never knew what vast plains

could exist between

adjoining rooms in one shall houseuntil she took in boarders.

She came to dread to look

into their room, knowingthey cared not one whit

for that which she had come

to think of as her daily bread.26

FRANK CAPUT

REMEMBERS HOWAT"The Yellow Dog Fund was kept up by a lot of yellow financiers to buy yellow legislators--and both buyers and sellers had a dirty yellow streak in them."John L. Lewis crucified Alex Howat--Appeal to Reason

with the Yellow Dog. Us that went along

with Alex lost our jobs, our entries, even

our tools. They took everything.

So we left for Colorado when Alex

went into Illinois and they passed

the Yellow Dog again that forced you

to give up your right to strike. Either

sign it or get going. We wouldn't sign.

We wouldn't work in a wildcat mine,

Mike and John Chiolino and me, but

after only a year I got hurt and

the Colorado mines dried up.

McQueen give me my job back--

Howat was out, John L. Lewis was in.

The big money won, you see.

Everything was hunky-dory then.

We got what the little boy shot at.27

NO PRIZE

For Janie Chiolino CaputWe worked in pairs, called ourselves brothers

(recalled Frank Caput, who wished he could get

the Western Coal & Mining Co. books to prove

his story of No. 23 Western at Minden). There was

me and Mike Chiolino, the Harrigans of Girard,

John and Louis Paffy of Franklin, a couple guys

from Frontenac, and two Austrians--one of them,

John the Bachelor, weighed 300 pounds, lived

at Edison. Mike and me got out early one morning

and Jim McQueen the Boss said, "Ain't you boys

in the race?" "What race?" we asked. "The one

to see who'll do the most work today," he said.We got to it. John the Bachelor in the straight

entry picked up a car with his bare hands and put it

back on the track. "Goddamn! We got no chance!"

said Mike. "Let's give it a try," says I. And believe

it or not, Mike and I won. Jim McQueen measured

that entry four different times to make sure, but we

had 96 foot of bushing, 36 foot of crosscut, 351

thousand of coal (about 150 tons), and 60 cars of rock

we wheeled. I'd go in, Mike would take care of the

empties and bushing. I'd drill an eight-foot hole,

shoot it, and get eleven foot of coal. . . . 100

and eight feet in all. No prize. But we won!28

THE WIDOW

MAKES A STATEMENT

For Dorothea WallaceWe were at a party having a good time.

We did not go to quarrel, for my husband

carried no weapon of any kind, I know. If so,

he certainly would not have taken me,

his wife, and child along.He was playing boccie, having a good time,

when a guy by the name of Pellegrino

called him aside to ask if it was so that

he was saying lies about him. My old man

said, "No. I do not lie."Pellegrino's brother-in-law, he stood nearby.

He started to insult my husband, called him shit.

My husband told him to be careful or else

he wouldn't like what he'd get. He turned

away to play his game.The guy shot at him, missed, and I cried

out as my husband throwed a ball at him, and then

the bastard fired again and hit my man, but he,

not feeling the wound, throwed another ball that

really hit him hard.It struck him in the forehead. My husband

walk over and hit him until he was too weak

to whip him any more. While my husband

was beating this man who shot him, Pellegrino

jumped him from behind.29 My husband's friends separated them, and then

my husband, finding out that he was shot, started

to run. Then I saw two of Pellegrino's cousins,

Enrico and Savirio, fire five shots at him!

I could not move.My husband reach the house where they dance.

He fell to the floor, half dead, and Savirio

took a poker, wanted to run it through my husband's chest

to finish him off. I saw a bottle. But before I could

strike that murderer. . . .A policeman grab me, took the bottle.

He cursed me, said I would go to jail. Savirio--

that policeman shook his hand, called him friend,

though he knew that coward had shot my man, he

still holding the gun.I want everyone to know that this party

that did the shooting were my husband's

best friends up to last September when

the strike started--my husband for Howat,

the others for the other side.My husband did not want trouble. The first

time he saw these men again was last Sunday,

when they killed him. My husband's last words

was you never know why your friends turn

out the way they do.30

THE KING OF THE MINERS

For Gale ShieldsHe was not an educated man

in the sense that he knew the law

or was certified to cure the ills

he saw, and one of his shortcomings

was that if he believed a thing right

he could see it no other way.The coal companies never got too big

for Alexander Howat to tackle.

The bigger they were, the harder

he fought, his defiance bringing

prosecutions which sent him to jail.

He became a power of the past.At his sentencing, miners stood up to join

the cry: "Jail one year--no work one year."

Though stripped of political power, he

remained armored in their love. Observers

saw "something in his fighting spirit

that even jail could not touch."31

DESERTED HOMESTEAD

For Roger O'ConnorSomebody's day lilies host the grounds

around this family's house. Abandoned, it stoutly stands,

its wardrobes filled with clothes, dishes in the pie safe,

the kitchen's calendar still reading June 1933.

Who now can say how its situation came to be

this uncared-for gray and penitential black?Perhaps there was danger within its well-built walls,

an engulfing emotion or unpublishable sin without rein,

possibly a simple death or a rainbow of wanderlust . . .

or a case of contagious disinterest. There was maybe just

no longer need or a greater necessity. Something

preceded this peaceful decay, moved a family suddenly.In this slant of sun, we think it leans as a repudiated

lover should: tenacious to the way things used to be,

devoutly disbelieving change of taste, resigned to obey

with grace the inevitable chemistry of the seasons.

It is a survivor by chance, for its joists are tempting

and its walls surely challenge the southern winds.For all these crowded hours of day lilies,

it must somehow have remained invisible,

revealing only protective reflections,

mirroring home to those who came to divest it

of its worth--or are those faces smiling

from the windows really ours.32

HOMETOWN BURIAL

For Ted WattsSaturday night friends set out to give Kid Jackson

a good send-off when he returned from K.C.

dead of T.B. All his gambling buddies were on hand,

the services almost over, when into the grave

jumps this hare. The ladies kinda gasped, but

that was nothing--compared to a minute later

when Little Bill and Joe Fat jumped in after.

It's supposed to be a lucky piece, you see,

the left hind foot of a graveyard rabbit, and

both them guys was gonna have it. The rabbit

didn't have no chance: lost his foot, over which

Bill and Joe started to rassle when somebody

hollered to auction it off--give the proceeds

to Kid Jackson's folks to help with the funeral.

Course, most folks knew Kid Jackson didn't have

no ma or daddy anymore, but everybody wanted

that lucky piece, so off it went to a Kansas City

dealer for fifty bucks, which Little Bill and Joe Fat

split, proving beyond a doubt that the left hind foot

of a graveyard rabbit certnelly brings good luck.33

HIGHLY

SOPHISTICATED

SWEDES

For Frances McKennaAs if forever

trees, sumac, blackberries

grow on these pits

where coal was stripped.

Deep waters now, a boy dived in,

came out with hundreds of clinging

cottonmouths. Such tales abound.

Despite deep miners' talk,

we know that multitudes of maidenheads

have shaped these shores

where fires have burned all night.

W.H. Auden was impressed.

Rebecca Patterson used to take

her Texas guests to see

these unnatural phenomena.

But, young bloods of Goshen,

we also have front yards in Kansas

yet and Methodist saints.

As for highly sophisticated

Swedes, you will meet one

almost anywhere. We have plenty.34

AGNES HOWAT

For John GarraldaAfter the Great War, my wife was proud

when I returned to Europe on a Socialist labor

mission, reporting directly to President

Woodrow Wilson. Five times I went.

She thrilled to hear the arguments

I posed to Ramsay McDonald, Clemenceau,

Kerensky, Trotsky, Stalin, Lloyd George.

She thought she had married an important man, so

it sort of made up for the times my men

called me the Bull of the Woods--which she

thought made me sound too free, especially

since she had no children of our own.

She blushed to hear it, but she stood by me

throughout the trials and pardons, the screed

of strikes and imprisonments; she went with me

when I was ousted from District 14.In Illinois, for a while she was lifted

when I became president of the Reorganized

Mine Workers' Union, but all but collapsed

when John L. Lewis broke us and we moved.

In '31 she put on her best hat

when I became contract investigator

under U.S. Secretary of Labor Bill Doak,

But John L. got to me again, so back to Kansas.

She weathered my post as inspector at the port

of entry between Pittsburg and Joplin, but

being a political appointment, that went caput.

I started drinking--heavily: I know it hurt

Agnes with her envolvement with the W.C.T.U.,

but what else was I to do? Each morning

her eyes are dry as she tells me good-bye

and I leave to sweep the streets of Pittsburg.35

III. A STONE DOORSTEP

"Childhood is simple and free. The spirit can grow boundlessly, but in older years it is warped and scarred trying to fit into rules and measures.

"A man looks back to escape the future. The goodness of childhood is gone, but he knows that is the answer to his wanting--to be simple and free again, to be as a child.

"So the place of his childhood becomes a symbol. He sets his feet on the rich green ground of memory and his heart is broken when he finds decay.

"But it is the decay of his own spirit he unknowingly grieves, and that is the one thing that is impervious to time. Wood and trees and fences decay.

"But a man's spirit can outlast a stone doorstep."--Zula Bennington Greene, Skimming the Cream (Topeka: Baranski Publishing Company, 1983), p. 56.39

WARNING

For Bill DuffySomeone must have loved the look of

trumpet vine and planted it

beside the chimney wall in all

innocence--having seen it blare

from some catalog page--not knowing

that its scarlet horn in a mere

three seasons would secure itself

along the chimney and grow a force

of roots beneath the house, drive

cracking tendrils through the walls,

spin delicate coils to lift the roof

above its waxy leaves. "Indestructible!"

the catalog should have read.

Withstanding first lye water, then

hatchet, it would thicken annually.Pity the unsuspecting bride who planted it,

who at first blinded by its size and strength

soon discovered that its obscene blossoms drew

more swarms of ants than flights of hummingbirds.41

ANOTHER LANDSCAPE

For Ray WheelerThe cottage with bay and thatch is gone.

A new brick house with straight lines sits

where Old Man Brunskill's cottage used

to stand, from which would pounce a furious

little dog on men and women of facts

and figures who, while ignoring the laughter

from his honeysuckle hedge, wondered

at seashells lining his gravelled path,

not knowing that those horns of Triton

satisfied an inland yearning for the sea.42

THE GARDEN OF EDEN

For Elizabeth LaytonIn Lucas a Civil War

veteran rebuilt the Garden

of Eden, guarded by an

Adam sixteen feet tall

and a fourteen-foot tall Eve. He

wears a Masonic apron.

Under his foot is the head

of a serpent who undulates

twelve feet tall for thirty feet;

Eve accepts an apple from

a serpent who undulates

on the other side for thirty feet:

these form the grape arbor,

every inch concrete. On the

wall Abel's wife mourns her

husband under an eye ball

whose pupil is an electric bulb;

Cain goes out from the Presence

of the Lord, driven by an

Angel, who carries

an American flag.

A soldier shoots an Indian,

which aims an arrow at a dog

who chases a cat who chases

a bird that is about to pounce

on a worm gnawing a leaf.

A girl chases the soldier.

In the background we see Christ

crucified by a doctor, a lawyer,

and a priest. Underneath

is a masoleum where the43 Union veteran lies

in his open concrete coffin,

at his feet a plugged concrete

jug, filled with water

when he died in 1932--to grab

on Resurrection Day, just

in case he had to go the other way.

All this for one dollar.

At eighty-odd the veteran

had married a twenty-three-year-old girl.

Two children were born

of this union. They played

under the Eye of God. The Civil

War veteran's handy man

changed the bulb whenever necessary.44

CATFISH LEGACY

For Mark, Wylie, and TomEdging through the snow

head to wind

my brother's three small sons

dog after him.

The pond they seek still beds

an eight-pound bullhead

my father is said

to have stocked there

the year before his death.On such a day as this

(although I sense it cannot be)

dreams should become reality.

They chop through ice

this morning not for thirsting cows

but for a glimpse of cat

mud-deep in his season's sleep,

their believing breaths

breaking shorter and shorter

in the icy air.45

THE STRANGER IN HER ROOM

For Lemuel NorrellIt was illogical

that she should enter her own house

to find him, a stranger, sitting in the dark.

But there had been such a sunset

he wandered in to use a window,

turned off the lamp to watch the sky,

and when it died he watched it still,

not hearing her steps, not realizing

her incomprehension of his sitting in the dark,

a smiling stranger, whose privacy

had been invaded.46

THE VISIT

For James TateA visit, once made, is intractable,

a modification of memories.

After twenty years I revisit a farm:

only a chimney belies

the house that homed

perfection once. Rocks now

the stones that then weighed tons,

ruins dwarfed

by magnificence of memory.Even the elm which my father said

housed bears is gone.

Nothing remains

complete tonight

except years of burying

I am afraid to forget.47

MRS. HAUGHAWOUT

REMEMBERS

E. HALDEMAN-JULIUS

For Norman E. TanisFinally came time to fulfill the longing

I had to write, but my words came back

with discouraging, calm regularity.

Then came his challenge on the edge

of a rejection slip: a challenge to sincerity,

to strength, to write something that would say

the things I had to say. Each better thing I wrote

(the meager life I lived, the frugal things I did)

brought kind and better comment. My life

glowed: I had aim and purpose. His name

was in my heart--constantly. But when I saw it

in a magazine one day in casual mention

showing that the world knew him as well as I,

my eyes were almost blinded. I found him

in Who's Who. I found a list of books

he had written, and then one day I saw

cited: "Independent, Vol. 155, p. 282,"

and there his portrait, "Voltaire from Kansas."

I suddenly feared to wonder why he cared.48

MOCKINGBIRDS

AND SALOONS

For Kenneth MelaragnoSaturday night streets crowded,

out-of-town drummers lauded

the virtue of Pittsburg's twenty-three

saloons, booze flowing all over

Broadway from First to Eighth Street,

smoke everywhere.Minister Harold Bell Wright

studied the exits from the bars

as he walked among the throngs

teetering along the plank sidewalks:

The men had looked upon wine so long

that their long faces had turned red.He saw Mrs. Jennings hang

her mockingbird outside

her store-front window; he saw

Jim Halliday, drunk, thrust his hand

inside that cage and take

the mocker as if it were his own.With screeching prisoner in pocket,

JIm Halliday entered a drug store

to have another "prescription" filled.

Wright saw Jim Halliday arrested

and, failing bond, hauled off

to the smelting town's city cooler.49 That night, Wright learned, Lyman Jones

and Seaver Jennings took Halliday

home to Carbon on his promise

to produce Mrs. Jenning's bird,

they not noticing a tiny breast

feather at the corner of his lips.While they talked to Mrs. Halliday,

Jim flew the coop, and Harold Bell Wright

preached a sermon next day

on mockingbirds and saloons, both temptations

on the main street to Heaven, both

befuddlers of our all too mortal senses.50

THE POLICEMAN

For C.W. BetzBrave, why he could go

into any bandit's hole:

the Public No. 1 Hero.

The Star played him up

for all his bravery.Then his death: shot up

by one of his mistresses.

She was about to become a mother

and wanted him to marry her.

He refused, so she shot him.She called the police.

They came, called his wife--

the first she knew he was married.

All were so let down--having such

great admiration for Speedie Stevens.A great personality he had

to be able to let them all down.

The Star was so let down

it told his story in a paragraph

of three lines on the obit page.51

MOTHER JONES

For Elliott ShoreHer age not known, she was always

young to the immigrant women--

always ready to explode--

a tornado sweeping through the coal camps

with a dangerous and unforgivable

truth, her appeal to reason memorized

by those who had never learned to run

their eyes over the pages of her voice.But once her voice whirled among them,

breaking open cellars of courage

drawn upon till then only to bear

hunger and servitude, the doors

of every miner's house in the district

flew open before dawn: their women

gathered, humbly armed, to storm

the mines with a convincing lightning.52

CLARK COUNTY

DIGRESSION

For Sharon E. NeetThe past is never easy.

No matter how painstaking,

how honest, we can never be

sure of it. . . . It slips.We know with certainty

that Granny Wild Holler,

whose name would sail

across the grasslands

in the Clark County Clipper

is dead. Yet, if we allow it,

we still sense her concern

as we read "Little Phoebe Holler

was quite ill this week"

or "Charles Holler and

his hands are down."Her fried chicken won a place

on the editorial page; everywhere

her sewing circle was well known

for its missionary quilts.

"Mother 1848-1915" is all her

tombstone tells, she really being

buried in microfilm at the Kansas

Cultural Arts Center in Dodge City.53

Gene DeGruson was born 10 October 1932 in Girard, Kansas, to Henry DeGruson, a French coal miner, and his wife, Clemence Merciez. He was reared in Camp 50 and on a farm near Weir. A graduate of Crawford County Community High School, Arma, he holds two degrees from Pittsburg State University, where he is currently [1986] an associate professor and special collections librarian. He has taught speech and drama at Highland Park High School, Topeka, and communications at the University of Iowa. He returned to Pittsburg State in 1960 to teach American literature, introduction to poetry, and research methods. During the summers he directed plays in the Tent-by-the-Lake Theatre, translating and directing Moliere's The Imaginary Invalid during the 1961 season.

Previous publications include a bibliography, Kansas Authors of Best Sellers, as well as contributions to First Printings of American Authors and Bibliography of American Literature. In 1975 he adapted Harold Bell Wright's first novel, The Printer of Udell's, into a melodrama, which he directed for the Pittsburg Centennial. He is currently at work on a "Guide to Special Collections in Kansas" with colleagues from Wichita State and Kansas State Universities.